[Press Release] Protecting Messengers of the Gods: Conservation of Nara Park Deer has Resulted in Unique Genetic Lineage

Protecting Messengers of the Gods: Conservation of Nara Park Deer has Resulted in Unique Genetic Lineage

The deer of Nara Park have distinct genetics that have been preserved for more than a thousand years, thanks to their protected status as sacred animals

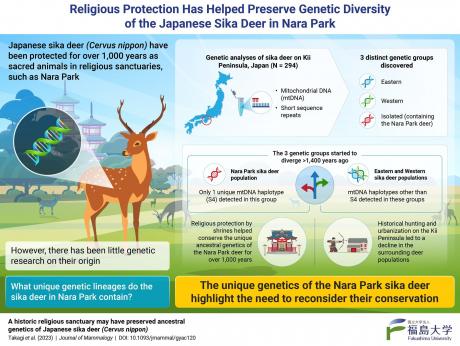

The wild sika deer of Nara Park are considered sacred. They have been protected for a thousand years in areas around shrines, where hunting is forbidden. Recently, a study by researchers from Fukushima University found that thanks to this religious protection (and isolation), the deer in Nara Park have a unique genetic lineage that differs from the genetics of the deer in the surrounding areas. Their findings could guide conservation and management efforts for these animals.

The existing wildlife of a region is heavily shaped over generations by environmental factors and human activity. Activities like urbanization and hunting are known to reduce wildlife populations. However, some cultural or religious practices have, on occasion, preserved local animal populations. For instance, the forests around religious shrines in Japan have historically forbidden hunting and, as a consequence, provide refuge for certain animal species. A well-known example of this is the Japanese sika deer (Cervus nippon), which has historically been considered a holy creature.

A revered animal that finds mention in many Japanese myths and ancient literature, sika deer have coexisted with humans for centuries. However, human activities like hunting and building settlements have led to fluctuations in their numbers. According to previous studies, Nara Park, located in Japan's northern Kii Peninsula, has been a sanctuary for the deer since ancient times. Hunting in the forests around important shrines in Nara, like the Kasuga Taisha Shrine and the Todaiji Temple, is strictly prohibited. These religious sanctuaries have thus functioned as protected areas and sheltered wild deer for over a thousand years. The existence of these protected habitats raises some interesting questions. For example, if sika deer have been protected in Nara Park for centuries, is the current deer population here genetically distinct from other sika deer populations in the area?

To seek answers to these questions, a research team from Fukushima University in Japan decided to take a closer look at the genetic structure and history of sika deer on the Kii Peninsula. The study, authored by Associate Professor Shingo Kaneko, along with co-authors Dr. Toshihito Takagi and former Professor of Nara University of Education, Harumi Torii, was recently published in the Journal of Mammalogy on 31 January 2023. Talking about the motivation behind this study, Dr. Takagi comments, "Legend has it that the sika deer in Nara Park had long been strictly protected as messengers of the gods. Today, these deer are one of the most popular tourist attractions in Japan. However, there has been little genetic research on the origin of these deer. Therefore, we conducted a genetic analysis of sika deer in Nara Park and the surrounding areas to better understand their origin."

The team collected 294 muscle and blood samples of sika deer from 30 sites on the Kii Peninsula between 2000 and 2016, and classified them into eight populations spanning the Western, Central, and Eastern Kii regions. The genomic DNA was extracted and analyzed for two genetic entities: short sequence repeats (SSR), which are inherited from both parents and tend to change frequently during evolution, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is only passed down from mother to offspring. The deer population was first screened for gene sets in the mtDNA that were inherited together, also known as a "haplotype". The team found 18 different haplotypes but with a low diversity across populations.

Using this information, they identified three distinct genetic groups, of which only one had a unique haplotype (S4), indicating a very restricted flow of genes across its maternal lineage. Interestingly, this isolated group included the deer around the Kasuga Taisha Shrine. "This could be possible as the female sika deer tend to migrate less and prefer to remain in their own natal habitat," explains Dr. Takagi.

So, when did these deer start to diverge from their ancestors? According to the authors, the Nara Park deer population split from their ancestors more than 1,400 years ago, around the exact time the Kasuga Taisha Shrine was established. The eastern and western groups, constituting the current Kii Peninsula population, more recently diverged from their ancestor. When asked what exactly caused the divergence and how they managed to maintain this distinct gene pool, Dr. Takagi says, "Generally, Japanese sika deer populations have been negatively impacted by habitat fragmentation and regional extinction owing to human activities. Our research shows that the religious protection helped rare ancestral populations of sika deer survive in Nara Park for more than 1,000 years, while the surrounding populations disappeared due to historical hunting and settlement."

As a result of the shrine's conservation efforts, the number of sika deer in Nara Park has increased. At the same time, the population of deer is increasing in the surrounding area, and the damage to agriculture and forestry is becoming severe. For the first time in centuries, they are in contact with deer in the surrounding areas, posing a threat to their preserved genetic identity. With this new piece of evidence, it is time to carefully reconsider their "conservation" based on the management plan, including the surrounding area.

Reference

Title of original paper: A historic religious sanctuary may have preserved ancestral genetics of Japanese sika deer(Cervus nippon)

Journal: Journal of Mammalogy

Image

Image Title: Unraveling the unique genetics of the Japanese sika deer

Image Caption: Japanese sika deer congregating in front of the Nara National Museum, Nara Park, Japan

Image Credit: Harumi Torii from Fukushima University, Japan, published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Society of Mammalogists.

Image Link: https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyac120

License Type: CC BY-NC 4.0

Usage Restrictions: Non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium is permitted, provided the original work is properly cited

Infographic

Image Title: Deciphering the unique genetics of the Japanese sika deer in Nara Park

Image Caption: Researchers from Fukushima University show that the sika deer in Nara Park have a unique genetic lineage which has been preserved for over 1,000 years, owing to the religious protection they have received from nearby shrines

Image Credit: Shingo Kaneko from Fukushima University, Japan

License Type: Original content

Usage Restrictions: Cannot be reused without permission

About Fukushima University

Popularly referred to as "Fukudai", Fukushima University is a national university with a main campus in Kanayagawa, Fukushima Prefecture. It was established in 1949 and consists of five faculties - Human Development and Culture, Administration and Social Sciences, Economics and Business Administration, Symbiotic Systems Science, and Food and Agricultural Sciences - and four graduate schools - Regional Design, Professional Teacher Education, Symbiotic Systems Science and Technology, and Food and Agricultural Science. Approximately 4,500 students study on the campus, while actively engaging in extracurricular activities such as clubs, circles, and volunteer activities.

Fukushima University attaches great importance to education and aims to produce graduates who can take up the challenge of addressing problems in modern society. The university's educational philosophy is "education based on problem solving,". Learning at Fukushima University is not limited to the acquisition of systematic knowledge from books. The students undergo holistic development by going out into the community, where they talk with residents and gain experiences that allow them to develop their own approach to identifying problems in the real world.

About Associate Professor Shingo Kaneko from Fukushima University

Shingo Kaneko is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Symbiotic Systems Science at Fukushima University, Japan. He earned his doctoral degree from Hiroshima University in 2008. His research interests include biodiversity and systematics, ecology and environmental science, and biological resource conservation. He has over a hundred research papers to his name and wishes to contribute to the conservation and management of wild animals and plants.

About Mr. Toshihito Takagi from Fukushima University

Toshihito Takagi is a researcher at the Graduate School of Symbiotic Systems Science and Technology at Fukushima University, Japan. He is the first and corresponding author of this article and his research interests include genetic diversity, wildlife conservation, and ecology and evolution.

Funding information

The study was funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grant number 19570081.

Media contact

Fukushima University

Public Relation Section

News